Conformation, Selection for Performance

and

Soundness Exam Procedures

HOW TO

TAKE THE COURSE

Hello, and welcome to your

Your instructor for this course is Don

Blazer. You can reach him by e-mail at:

donblazer@donblazer.com

You are now on a special link which

allows you to view, save or download the lesson. At the end of the lesson you will take an

exam and maybe have some outside assignments.

You can complete the exam and assignments online and simply click

“submit” to send your work to your instructor.

You will be graded on your efforts to

communicate clearly. Your spelling and

grammar will be graded and spelling errors will count against you. Your instructor will evaluate your

understanding of the material presented.

An “A” grade means your work is

outstanding. A “B” grade means your work

was above average. A “C” grade means

your work was average. A “D” means your

work was below average, and while you will be sent the next lesson link, you

should reconsider your study habits. An

“F” grade means you will not be given the next lesson link until you

demonstrate for your instructor you have reviewed the material and are ready

for a second examination.

To achieve the best results, read each

lesson at least twice. If you have a

specific question, or you don’t understand the material, contact your

instructor for clarification. Don’t let

your questions go unanswered; one of the advantages of online courses is that

your instructor can work with you one-on-one to be sure you understand the

information being presented.

Some courses do not require you to

work with a horse, but after reading some of the lesson, it is a good idea to go

out and observe a horse or horses and practice the techniques you are

learning—if that is possible. Try to see

the things being discussed, and how they work.

Observation is one of the greatest keys to success whether training,

trading, feeding, or examining for general health. Look and work with your horse and look at

other horses—but when watching them perform, see more than the surface—see the movements,

see the personality, see the strengths and weaknesses of each individual. And then try to apply some of the things you

have just been reading to the horse with which you are working. This is the best way to reinforce your

understanding and assure your success.

Your instructor will grade your quiz

and send an e-mail to you with comments and suggestions. You will not receive the link for the next

lesson until your instructor is satisfied you have mastered the preceding

lesson.

When you receive your next lesson

link, study that lesson just as you have the preceding lesson.

You are working toward a Bachelor of

Science in Equine Studies degree. This

is not an easy program just because it is online. All Success Is Easy course instructors are

experts in their field. They are proud

of their accomplishments and their reputations, so they are demanding of

you. They want to assure your success by

making certain you have as good an education as possible. They want to be as proud of you as you will

be of yourself.

When you receive your

Conformation and Selection

For Performance

By Don Blazer

Copyright © 2003

What

a horse does best is move.

His

efficiency of movement is the foundation of his survival, his evolution, his

beauty and his grace.

By all accepted standards, what we say

is "good conformation" is said specifically as it relates to the

horse’s efficiency of movement.

If

our desire is efficient movement, then the ideal conformation is the form which

best achieves efficient movement. And by its very nature, it is also the form

which most assures continuing soundness.

But efficiency of movement is not

always what we want.

Various breeds accentuate certain

conformational traits which affect movement, and particular performance

disciplines demand distinctive variations of movement. So the desire for

efficiency of movement is replaced by another desire. The new movement desired

always subjugates efficiency. And over a period of time the various desired

movements result in conformational changes. The changes in themselves are not

necessarily right or wrong; they are simply choices. But all choices which

limit natural efficiency of movement come with consequences.

Understanding a horse’s conformation,

and the deviations from the established standard, allows you to recognize how

and why a particular horse moves as he does. And with that understanding you

can choose the performance work most suitable for that individual.

There are two ways to judge a horse’s

conformation.

One: determine the correctness of the

form as it relates to efficiency of movement. (This is supposedly how halter

horses are judged--form as it meets the breed standards. Halter horses of any

breed seldom reflect efficiency of movement, instead portraying the

"beauty" of the current fad, which is correct if meeting the

standards of a new desire.)

Two: determine the strengths and

weaknesses of a particular conformation as it relates to the performance

desired. (Selective breeding has been successful in producing horses with both

conformation and talent for specific exercises. Knowing what performance you

want from a horse allows you the opportunity to select by breeding, the natural

desire to work, and by conformation, the natural ability to work.)

Always keep in mind that a horse’s

action is initiated in the hindquarters. The hindquarters is

the power plant of the horse, the driving force. The forehand catches,

rebalances and stabilizes the horse. The conformation you are seeing (forehand,

hindquarters, overall) should be evaluated either in relationship to how well

it can function in performing the desired movement, or for its contribution to

efficiency of movement.

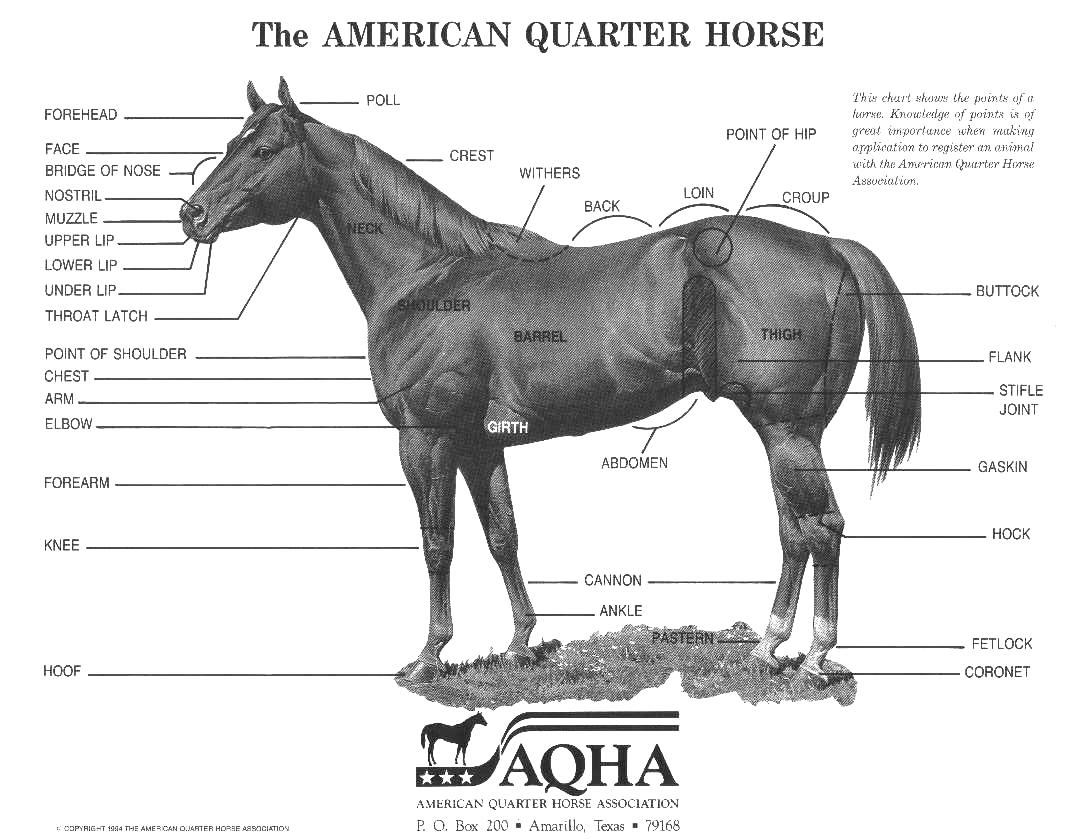

View a horse’s conformation from three

positions "directly in front of the horse, at the side of the horse and

directly behind the horse. Looking at the horse head-on allows you to see the

width of the forehead, the chest and the alignment of the front legs. Looking

at the horse from the side allows you to view the set of the head and neck, the

top line, the underline and the positioning and angle of the legs. Standing

directly behind the horse you can see alignment of the hind legs, the level of

the hips and the straightness of the spine. (To fully see the spine, it may be

necessary to stand on a platform to elevate your view.)

FEET

If I am looking at a horse for

possible purchase, I will stand in front of the horse and look at the coronet

bands of both his front and hind feet. I want to see an even coronet band,

symmetrical with the opposite one. The coronet band should flow across the

front of the foot and should not have dips or upward variations. The hair line

should move evenly around toward the heel and should not sink down toward the

ground. Any deviation in the hair line at the coronet band tells you there is

something going on of concern.

Keeping

the coronet band as the main focus, I can view the entire hoof. I look for

flares, differences in the angle of the medial and lateral hoof wall, pulled in

heels and hoof wall damage.

Moving

to the side of the horse I look for dorsal/palmar

(front to rear) balance. Determine if the horse has a broken forward or broken

backward hoof/pastern axis. Carefully analyze the angle of the hoof wall horn,

noting any tendency toward under-run heels.

I

then pick up each foot and look at the medial/lateral balance, the condition of

the frog, the medial/lateral heel lengths, the position of the bulbs of the

heel, and the width of the heel.

A

horse with small feet can do just about anything, but his soundness will be

questionable, especially if he is asked to work in high impact events.

Flat

footed horses should be worked only on soft footing.

Mule

feet are narrow with steep walls. A horse with mule feet should be worked only

on soft footing.

Coon

footed means the horse has a very upright foot, while the pastern slopes

radically toward the hindquarters.

Club

feet are defined as a foot with high heels and a front face which exceeds 60

degrees. Club feet can be genetic, caused by the horse having one leg shorter

than the other, or faulty nutritional practices with young horses.

Contracted

heels and small frog are common results of poor shoeing practices. Horse with

such problems should be used only in non-concussion events.

Narrow

hoof walls predispose the horse to sore feet and are often associated with flat

feet.

Without

a foot, the rest of the horse’s conformation matters little. If the horse has

too many obvious foot problems, I don’t have an interest in purchasing him.

While most foot problems are the result of poor care and/or poor shoeing, many

will be associated with conformational faults.

If

I have been asked to evaluate the horse, I simply note my observations of the

hoofs and move on.

HEAD

Return

to a position in front of the horse and study the horse’s nostrils. I want to

see a large nostril, capable of opening wide to allow maximum air flow. A great

air supply is extremely important to any horse which will be used in activities

requiring speed and stamina. (Racing, cutting, jumping, eventing.)

The

more air a horse gets into his lungs, the more oxygen the blood carries to the

muscles, having a direct effect on the horse’s ability to perform.

A

horse with small nostrils should be considered for pleasure riding or trail.

It is best if the horse’s face is

neither dished nor bulged out. A smooth, straight line from a point between the

ears down the nose to the nostril allows air flow. A dished face is a major

restriction to air flow and severely limits the horse’s ability to perform with

speed or stamina. A bulging face line (Roman nose) interferes with the horse’s

ability to see clearly and is usually associated with horses of poor

temperament, willfulness or spookiness.

A

large, soft eye set to the side of the head generally allows the horse to see

well, and is associated with a horse of kind temperament. Small eyes, often

called pig eyes, restrict a horse’s vision. The horse has both monocular and

binocular vision. He can look at two different things at the same time, or he

can use both eyes to concentrate on a single point, so what he sees can be

quite distracting to him. In addition, the retina of the eye doesn’t form a

perfect arc, so the horse must frequently shift his head position to bring

particular observations into focus.

It

is not advisable to have the eyes set too far to the side of the head, as this

causes the horse even more trouble bringing things into focus. It is also much

more difficult for the horse with wide-set eyes to focus both eyes on a single

object, which in turn limits his ability to concentrate.

A

horse with a well defined jaw line usually has a relatively wide jaw, which is

an asset. Make a fist and place it between the horse’s jaw bones at the

throatlatch. A horse of one year or older will have what is considered a wide

jaw if you can slide four knuckles of your fist between the jaw bones. This

width allows for good air flow.

With

width between the jaw bones, the throatlatch will be clean and well defined. A

well defined throatlatch is important since everything essential to the horse’s

performance--blood, nerve impulses from the brain, air--travels through this

area.

Horses

which are narrow between the jaw bones should be directed toward performances

not associated with speed or endurance.

NECK

The

neck is measured from the poll to the withers and should be about one-third the

length of the horse’s body measuring from the tip of the nose to the buttock.

The neck should be set on the horse’s chest neither too high, nor too low, but

aligned for forward movement.

A

short neck does not affect the length of the horse’s stride, does allow for

quick air flow to the lungs, and does aid in the horse’s ability to make quick

changes of direction. A short neck is not considered advantageous for a jumper

or for a horse expected to work with speed for long distances. However, a horse

with a short neck gets plenty of air to sprint and will usually have the

lateral agility needed to cut cattle.

A

long neck causes the horse to be heavy on the forehand, but is acceptable in

jumpers and horses working in straight lines.

An

upside down, or ewe neck relates to high head carriage and compromises all

performances. A horse with the upside down neck is often called a

"stargazer", and is often under-conditioned because it is difficult

for him to engage his hindquarters. Ewe necked horses are frequently underweight

and many have a bulging underline.

The

horse with a large crest or "crest fallen" neck is usually the

product of obesity, which, of course, can be corrected.

A

bull neck is a heavy neck with a short upper curve. Horses with this

conformation generally work best in harness.

Horses

with a swan neck--almost an "S" like curve--never work well on the

bit and often tuck their chins to their chest. This neck generally has a long

dip just in front of the withers.

A

naturally arched, well-defined neck is suitable for any type of work.

THE

BODY/WITHERS

When

examining the horse’s body, begin with the withers. The withers are formed by

the coming together of the left and right scapula, which don’t actually touch,

but are held in place by muscles.

If

the withers are rounded, flat and with little definition, they are called

"mutton withers." Mutton withers affect all physical action and allow

no free flow of movement. Saddles slip easily on mutton withered horses.

High

withered horses are hard to fit with a saddle, but can generally perform any

kind of work.

THE

BACK

The

horse’s back lies behind the withers and to the loin, which is defined as the

last rib to the point of the hip. The loin is considered to be long if it is

more than a hand’s length.

A

hollow back looks concave and can be rider induced due to a lack of drive from

the hindquarters. Riding with incorrect contact, a pull instead of a push,

creates the low back and a strung out horse. This condition is often seen in

horses used for distance trail riding.

Short

backed horses have limits to their lateral flexion, and therefore generally

lack suppleness.

A

roach back--the spine raises in the loin area--is often associated with

stiffness in the back. Roach backed horses cannot use their loin properly and

so they are limited in quick lateral movements.

Long

backed horses generally have a weak loin area. The weakness here precludes them

from "folding" (drawing their hind legs forward under them) quickly,

so these horses lack both speed and power.

A

horse is said to have "rough coupling" if he has any kind of a

depression in his back just in front of the croup. Rough coupling can be

compensated for by being sure the horse is very well conditioned.

THE

CHEST

A

horse with a wide chest can do just about anything, but the width will often

adversely affect the horse’s length of stride and speed. Look for a horse with

a chest proportional to his overall look. If you immediately notice the horse

has a wide chest, he probably has a little too wide a chest.

RIBS

Standing

in front and just a little to one side of the horse, you should see

"well-sprung" ribs, meaning the ribs are prominent at the heart girth

area. Well sprung ribs taper in as they approach the horse’s flank.

Barrel

ribs are prominent all the way to the flank. The horse has a body "like a

barrel." This width all the way to the flank generally accounts for an

uncomfortable ride, because the horse cannot easily bring his hind feet well

forward and under his body.

Pear

shaped ribs are narrow at the heart girth and widen toward the flank. A horse

with pear shaped ribs should be used on level terrain and cannot be expected to

do a lot of work. As the barrel ribbed horse, he cannot easily bring his hind

legs forward.

FRONT

LEGS

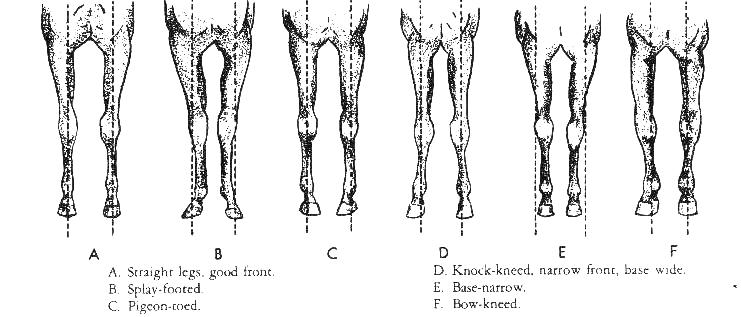

Looking

at the front legs from the front, you should see the form of the bone entering

the joints in the center.

A

horse with a base narrow stance cannot be expected to perform well in speed

events or events which require athletic agility.

Base

wide horses are best suited for easy pleasure riding.

Horses

which toe-out can be used for high impact events, while horses which toe-in

should be used only in low impact activities.

Move

to the horse’s side to evaluate the horse’s shoulder. An upright shoulder

indicates the horse can work in sprint activities. The horse’s speed lies in

his ability to gather and get into the next stride, not on the length of the

stride. In other words, the more strides within a particular distance, the more

speed. A horse increases speed by driving off the ground. His speed slows as he

travels through the air.

If

the horse has a sloping shoulder, his withers will be well behind his elbow.

Horses with this conformation are well suited for jumping, dressage and

driving.

A

long arm produces speed, but is also excellent for the dressage horse.

A

short arm "from the point of the shoulder to the elbow" will create

an angle of less than 90 degrees.

A

long forearm favors speed and jumping ability. The horse with

a short cannon will generally have speed, agility and foreleg soundness.

From

the side you can determine whether or not the horse is over at the knee or back

at the knee. Back at the knee conformation is frequently associated with

unsoundness, but is also the desired conformation for the modern western

pleasure horse as he will move slowly with flat knees and little reach.

Over

at the knee horses are not pleasing to look at, but many have speed and seem to

remain sound.

Look

at the horse from the front to see if the horse has bench or offset knees. A

horse is said to be bench kneed when the forearm enters the knee to the left or

right of where the cannon bone exits the knee, making the forearm the back of

the bench, the knee the bench seat and the cannon the bench legs.

An

offset knee has both the forearm and the cannon entering and exiting the knee

either on the medial or lateral side.

The

fetlock joint should be clean and well defined.

A

horse with long pastern provides a smooth ride and makes a nice pleasure horse

or dressage horse.

Short

pasterns contribute to a harder ride, but also aid a horse’s speed.

HINDQUARTERS

Stand

at the side of the horse to begin your evaluation of his hindquarters.

The

perfect length of the hindquarters is 30 per cent of the total body length and

is measured from the point of the hip to the point of the buttocks.

A

short hindquarters"less

than 30 per cent of body length"is associated

with a horse which lacks speed and power. Remember, all action initiates in the

hindquarters.

CROUP

A

flat or horizontal croup is associated with a flat pelvis. The topline of the horse continues all the way to the dock of

the tail. Horses with flat croups"which are

quite common"have a flowing stride at the trot.

They are especially good at distance trail riding, and driving in harness.

A

steep rump is called a "goose" rump and is not particularly common.

Horses with a goose rump are best suited for slower types of work, such as

pleasure or trail riding. The steep slant of the pelvis shortens the backward

swing of the leg.

Narrow

hips limit the amount of muscle the horse can carry, thereby limiting the

amount of muscle power possible.

A

"knocked down" his is when one hip bone is lower than the other. The

condition is fairly common. When examining the horse from the rear, be sure to

watch carefully as he is walked away from you.

A

long hip is easily recognized when the stifle joint sits at or below the sheath

line on a male horse. Low stifles are particular good for horses which are

intended for eventing or show jumping.

A

short hip creates a high stifle joint. Horses with high stifles are best suited

to draft work.

A

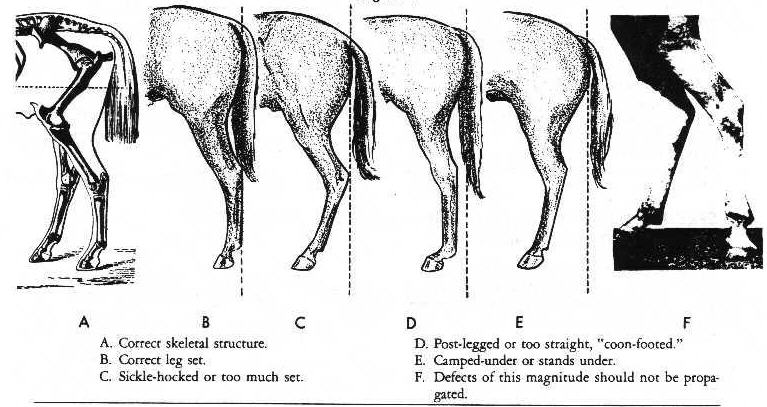

short gaskin is associated with high hocks, which generally means the horse

will have inefficient movement, taking an extra long stride.

High

hocks make a horse suitable for trail, pleasure riding, or driving.

A

long gaskin is associated with low hocks which often puts the horse is a

camped-out position. Horses which are camped-out behind lack power and

smoothness. He can best be used as a trail horse or pleasure horse.

The

gaskin length is best when it sets the hocks at the same level as the horse’s

knees, for the horse will usually have both power and speed. When evaluating

the potential of a horse which will be asked to work with speed and agility,

look for hocks which are at the same level as the knees.

Sickle-hocked

horses should not be considered for speed events, while post-legged

horses--very straight hind legs--are particularly good at speed events, but

little else.

A

horse is said to be cow-hocked if when viewed from behind the cannon bone and

the fetlock joint are well to the outside of the hocks.

If

conformation is demanded in relationship to efficiency of movement, a horse

will tend toward a natural, but moderate, cow-hocked stance. The horse’s toes

should point outward, and he should NOT stand square behind as virtually all

conformational standards require.

When

a horse increases his speed, the hips and the hocks rotate outward, and the

hoof rotates inward. A horse which stands square behind naturally--and they are

very, very rare--will strike his front legs with his rear feet when he moves

with speed.

Never

allow a farrier to trim a horse’s hind feet high on

the inside to make the horse stand square behind.

Do

not endorse breed association rules of showing which allow a handler to

"pull" the horse’s hocks out, twisting the foot into a straight

forward position. That is not the horse’s conformation and it is ignoring the

truth if it judged that way.

BALANCE

A

horse is said to be balanced when his withers and croup are level. A balanced

horse is generally capable of working any type of event.

Light

boned horses should work low impact and low speed events, while course boned

horses are more suitable to high impact events such as eventing.

LEG

JOINTS

The

joints of both the hind and fore legs should be clean and dry in appearance.

Any puffiness or signs of fluid indicate joint damage and eventual problems.

The

pasterns, hind and fore, should be tight and dry.

FINAL

ANALYSIS

View

the horse from the front, the side and from behind, looking at the entire horse

as a single object. Do you like what you see? Is he smooth in overall

appearance, or does some angle or roughness jump out at you?

As

you decide on the importance of each conformation point you have viewed,

evaluate you observations in relationship to efficiency of movement, or to the

work you want the horse to do.

Every

horse can do everything and anything to some degree. But mediocrity in

performance seldom pleases the horseman. So it is the responsibility of the

horseman to understand how the form affects function, and to select the correct

conformation for the work to be done.

It

is a bad horseman who demands a horse work at an event for which he is not

properly conformed.

Conformation

is visible, but the thing which makes performance champions cannot be seen. A

horse’s heart to compete and win can carry him super efforts, but he moves to

the victory stand on his correctness of form.

Quiz

Answer as True or False:

1. Breed associations establish

conformational standards.

2. Conformation standards assure the horse’s

soundness.

3. If the horse has good conformation, he’ll

be a great performer.

4. Judge conformation only as it relates to

efficiency of movement.

5. View a horse’s conformation from front,

side and rear.

6. A pretty head assures correct

conformation.

7. An upside-down neck is associated with a

high head.

8. High withers make saddle fit difficult.

9. A big, wide chest is very desirable.

10. A

long arm produces speed.

11. A

horse “over” at the knee is unsound.

12.

Short pasterns are bad.

13. The

perfect length of the hindquarters is 30% of the total body length.

14. A

short hip creates a high stifle.

15.

Horses are naturally slightly cow-hocked.

Write

a conformational report on a horse, and include an evaluation of what he might

be best suited to perform. Explain why.

Please e-mail all quiz answers to donblazer@donblazer.com.

Include ‘Conformation Lesson One Quiz’ in the subject

line.